Bologna is a place where the irreverence of students and trendy hipster young people meets the established, dogmatic aesthetics of Classicism and Catholicism. More generally than that, historic cities like Bologna (Italian and not) are places where living, breathing, active people navigate around historicised, dogmatised, dead (?) Culture, art, and architecture. This is a strange thing, a particularly Old World thing, hard to imagine for Australians and Americans (to generalise). The idea that someone can go to church weekly among centuries-old paintings, live in a centuries-old building, drive through centuries-old porte, smoke in a centuries-old courtyard or piazza, all while having to do the very immediate, undignified, living-people things like eating and shitting and driving and smoking and swearing and spitting and scratching one’s leg.

While walking from the park I come across a faded fresco next to a doorway. The fresco has been interrupted by a pragmatic apartment buzzer, shiny and gold in its newness and in its incredibly practical purposes. The fresco, despite having a buzzer-sized bite taken out of it, is covered in glass to protect it, maybe from different buzzers looking for a home. We have to keep this little slice of history safe. But we still have to get into the building.

Ruby and I are drinking some spritz mistos (Cynar + Campari) and eating some patatine gusto porchetta alle erbe and sitting in Piazza San Francesco and watching the sun slowly leave the façade of the church. There are always people around this piazza, which boasts a paved section, plenty of benches (rare for Bologna), and a grassy area, notably a group of youths of about 14 who do bike tricks and play loud music to impress each other. There is also an English couple about our age meeting up with two friends, a man in a striped t-shirt with a yellow bike, a guy with glasses drinking a beer, an old man with a hearing aid watching on, and a plethora of pigeons. In the middle of the piazza, on the paved section, there are usually groups of kids, anything from toddlers to older brothers in their 20s. Today is no different. There are three 11-or-so-year-olds kicking a football as hard as they can onto the façade of San Francesco and kicking it again when it bounces back. Sometimes they almost hit people. Other times their ball goes awry and they need help kicking it back. But in general they hit the building and it makes a loud thudding noise and one wonders how well this 13th century church can withstand this schoolboy violence (of course the answer is: quite well). Ruby and I talk about what she names the “desecration of sacrality in the name of fun,” embodied by these boys, and how it reminds us that Italians are able to or maybe have to not take themselves and their history too seriously otherwise they wouldn’t really be able to do much.

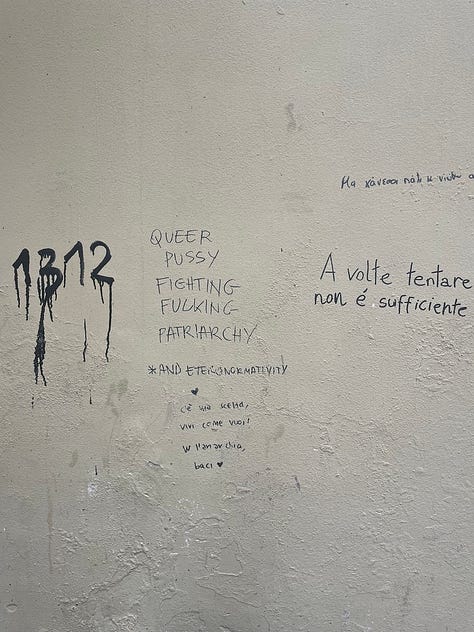

Graffiti is a big thing in Bologna probably because of the student population and the general self-ascribed fuck off!/vaffanculo! attitude. Some of it, I would venture to say most of it, is pretty hideous: ugly tags, horrible drawings, fake deep quotes, meaningless political slogans, interruptions of the majestic red-orange-green colour scheme of the city. But, if I’m looking favourably or at least understandingly at the boys who kick footballs at ancient walls, I can extend that favour to taggers and fervent political graffiti artists because it’s kind of the same thing. Irreverence to dogma. Living around dead buildings. Figuring out what your relationship is to history (it can vaffanculo, maybe). The apartment buzzer, the football, the spray paint, are all kind of part of the same impulse.