In San Vito Lo Capo in early May we had the perfect two-bedroom Airbnb from which you could (quite well) see the sea and could (very well) see a big road and a lot of construction. Our apartment stood singular, surrounded by rubble and sun-bleached dust, like photos of frontier houses or late-19th century pictures of stand-alone buildings in undeveloped uptown Manhattan (see figure). We were living in our own, 5-person enclave, with no neighbours to complain about noise and a great view from our balcony to watch the comers and goers on the big road.

On Saturday morning, while having our sleepy, slightly hungover morning coffee, bad Sicilian pastries, and fabulous fresh fruit, a funeral procession passed us on the big road. The sound of the brass band grew slowly as they made their way from the main part of town out to us and then past us. The music was grand and morose and apt. Traffic was stopped by a man in high vis. German cyclists stopped to watch. We stopped gabbing at each other to listen. It felt very seminal in the same way that entire short Sicily trip felt seminal, like if it happened in a movie we’d talk about the symbolism of the spectre of death for people celebrating a 22nd birthday or the significance of decadent Americans faced with the grand, morose, fervent Italian life cycle. We went back to our moka coffees.

Later that day, we walked to the end of the peninsula to the lighthouse. The sky was completely clear. We took a wrong turn up a hill towards the cemetery gates which were ajar and we wandered in. It became clear that the cemetery was open because the funeral procession had led here. A small group were at the back and others were leaving, they told us we could stay but the cemetery would close soon. The sky was so blue and the experience of being in an Italian small-town cemetery was strange. Most of the graves in the main section of the cemetery were from the 19th and 20th centuries: all of these people spent most of their lives around here, the rocky outcrop that defines the San Vito Lo Capo skyline and the smell of saltwater and the taste of swordfish were familiar to them. There were people who were born in the 1880s who lived until the 1960s. There were people who’d been sentient before the unification of Italy and still lived long into the 20th century. We talked about what an all-encompassing life that would have been—the ability to know life before and after radical modernization. The first Italian feature film was made in 1911. Commercial aviation and radio began in earnest in Italy in the mid-1920s. Two world wars happened. Fascism happened. Liberation day happened. In the 1940’s, Italy relinquished their colonial empire in Africa and Asia. The first Sanremo Music Festival was in 1951. Official television broadcasting began in 1954. The Beatles toured Italy in 1965. And everything else.

The cemetery visit struck me because of these people who’d lived long and complicated lives in, what seemed to me as a tourist, an uncomplicatedly beautiful little town. It struck me with anxiety also because I was very anxious about getting in trouble for sneaking into the cemetery and I was terrified of seeming disrespectful or oblivious (I was dressed for the beach, not for a funeral). But the thing that was most unique to this place was something about the graves themselves: each grave, almost without exception as long as the grave was at least late-19th-century, had embedded into it a photograph of the person or people it was dedicated to. Very serious photos: front on, stiff, serious. The pose told us nothing but the face told us a little bit. This is of course a common way that photos from early photography always looked, sitting for photos was slow and awkward and the photos came out quite uniform.

Only the newest graves were different. One dedicated Nicolo, a 19-year-old who passed in 2013, had several images: one of him smoking a cigarette leaning against a wall with a buzz cut and sunglasses, the others, selfies in his car, with a backward hat, with his tongue out, blowing a kiss, doing a heart sign with his hands. But Italians, on the whole, are attracted to the very traditional kinds of portraits on graves and tend to have kept it up. This kind of front on awkwardness is not only a 19th-century invention, portraiture has had a very Italian bent since Roman times and the Renaissance. Death-related portraiture reminds me so clearly of a painting I studied for A-Level, Botticelli’s painting of Giuliano de' Medici which was likely painted after his murder. The open window and mourning dove symbolize death while there’s a theory that painting is taken from a death mask, which would explain the almost closed eyes. From the US National Gallery website, “Botticelli's painting may have been the prototype for others, and lent symbolic gravity to Guiliano’s passing, showing him as an icon, almost a saint.”

Does inserting a photograph of a dead person into the stone above their dead body lend their passing symbolic gravity? Does it turn them into a saint? They do certainly follow a prototype. It facilitates an immediacy to death that reminds me of my trip to see Sant Caterina Vigri’s uncorrupted body at Corpus Domini. It’s strange for me, but it’s familiar to Italians.

On the streets of Italian towns, pasted on public buildings and churches, you will find epigrafe, or funeral notices. There are some on the way into central Rimini and I spotted one in Ferrara. They are, in some ways, a practical announcement of a death and an upcoming funeral, an invitation to attend for the entire community. They act as a substitute for a death notice in a newspaper. And they also feature images

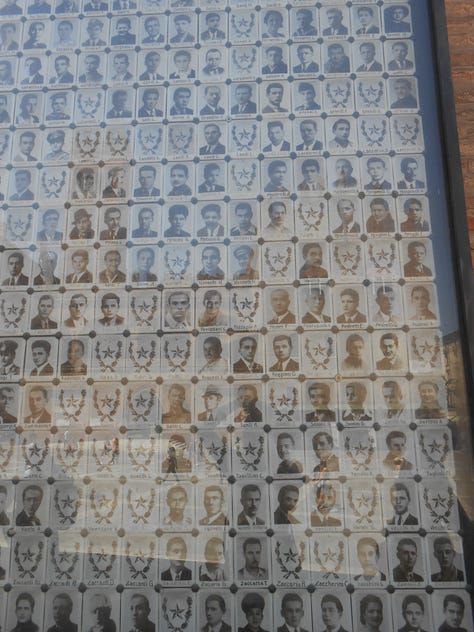

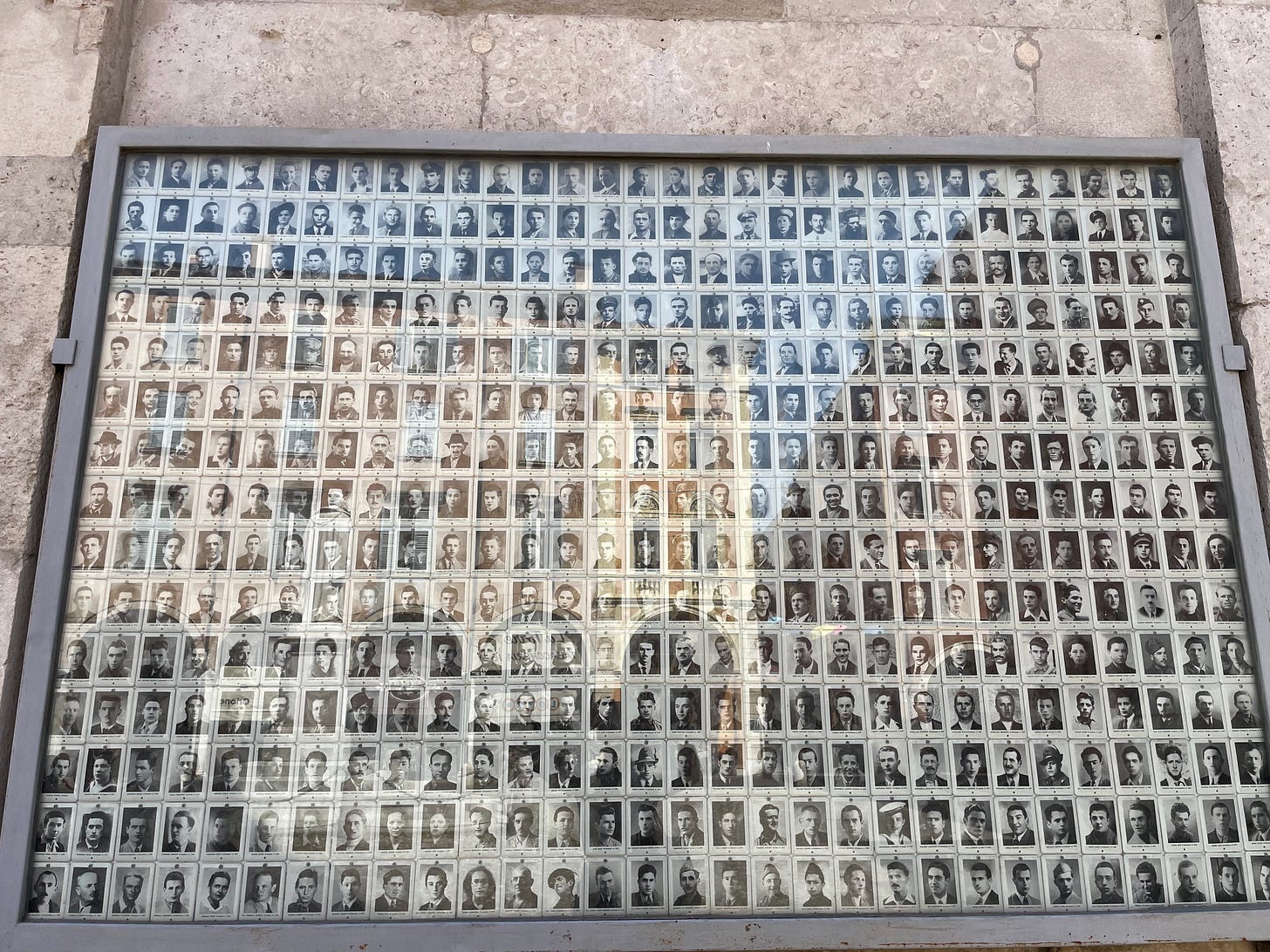

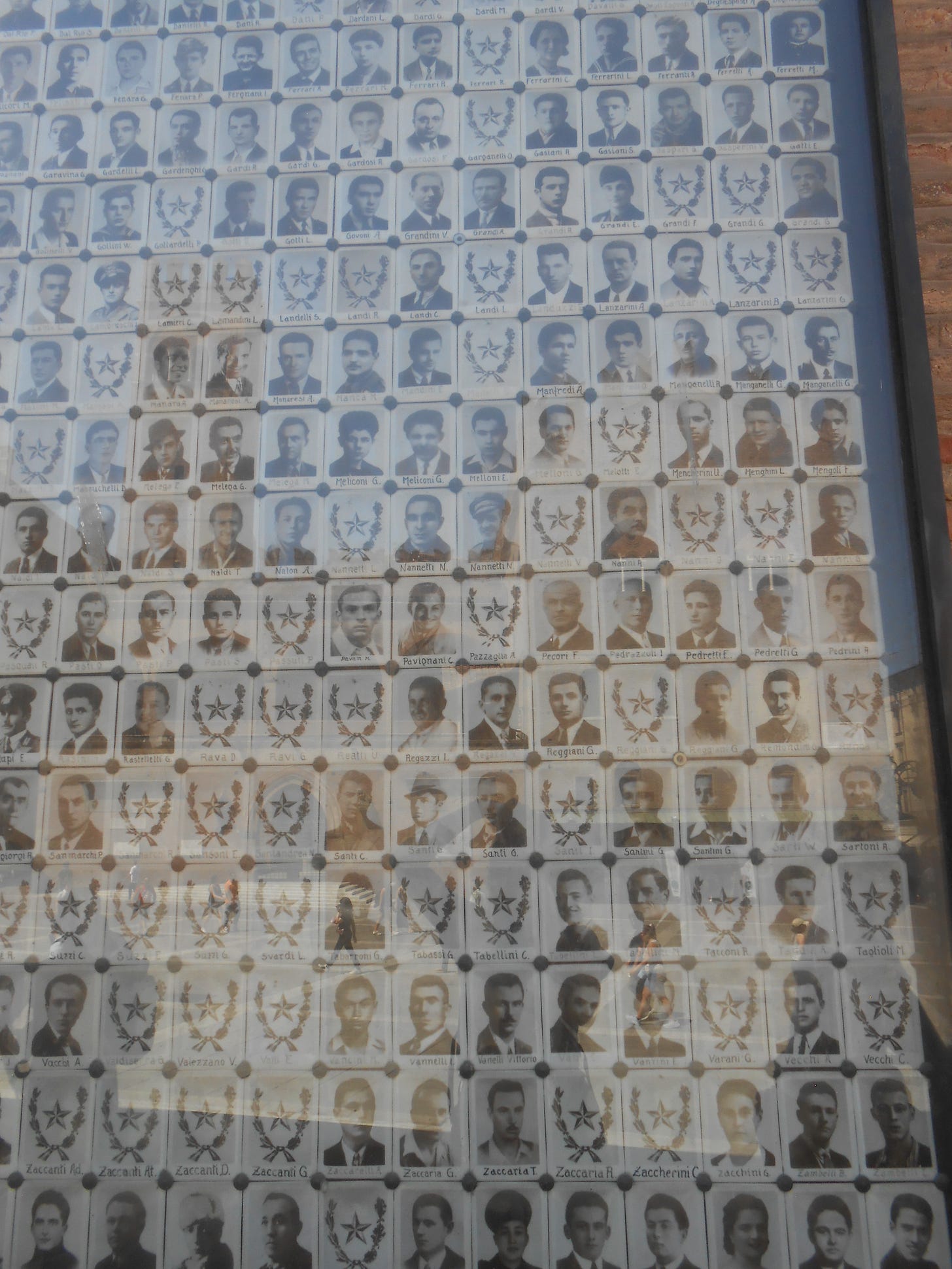

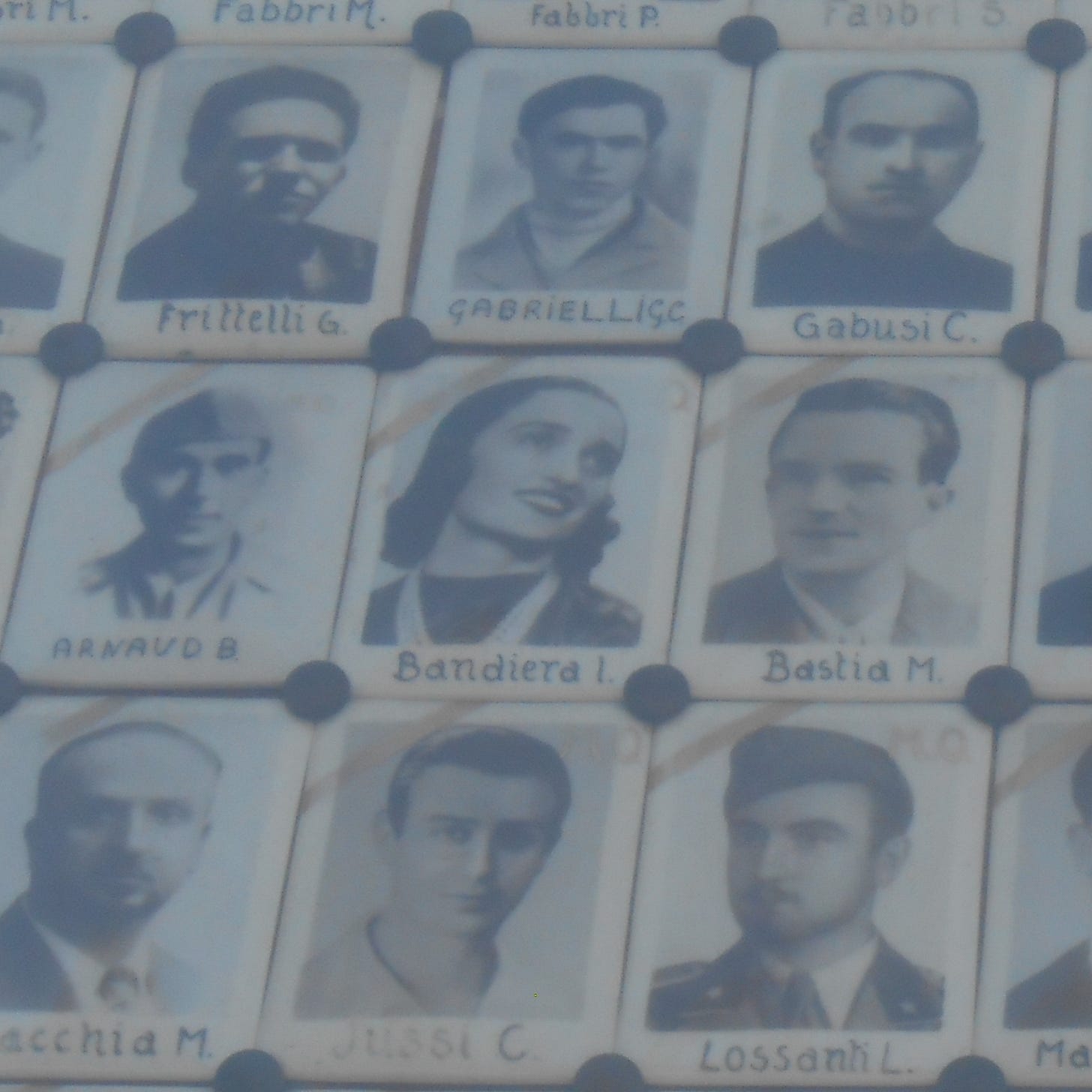

.In Bologna and Modena, two sites of strong Partisan movements (anti-nazi fighters in the national liberation war), there are almost identical monuments to Partisan fighters. Unlike what I would imagine a monument like this to be, a list of names and an inspirational quote, both monuments are made up of photo cards with pictures of each Partisan. It’s a very moving site, because it brings home the idea of collective action when you can see these faces in an eternal crowd of resistance.

Some faces have a huge amount of personality, like Irma Bandiera who is awarded with a gold stripe on her image and who is looking up, smiling, wearing lipstick and pearls. In 1944, she was captured, blinded, killed under torture, and her body was thrown into the street. Her smiling face is still in the street, or rather in a piazza

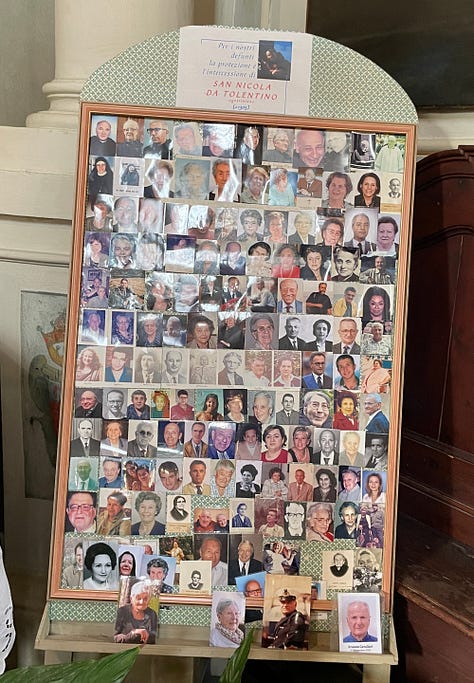

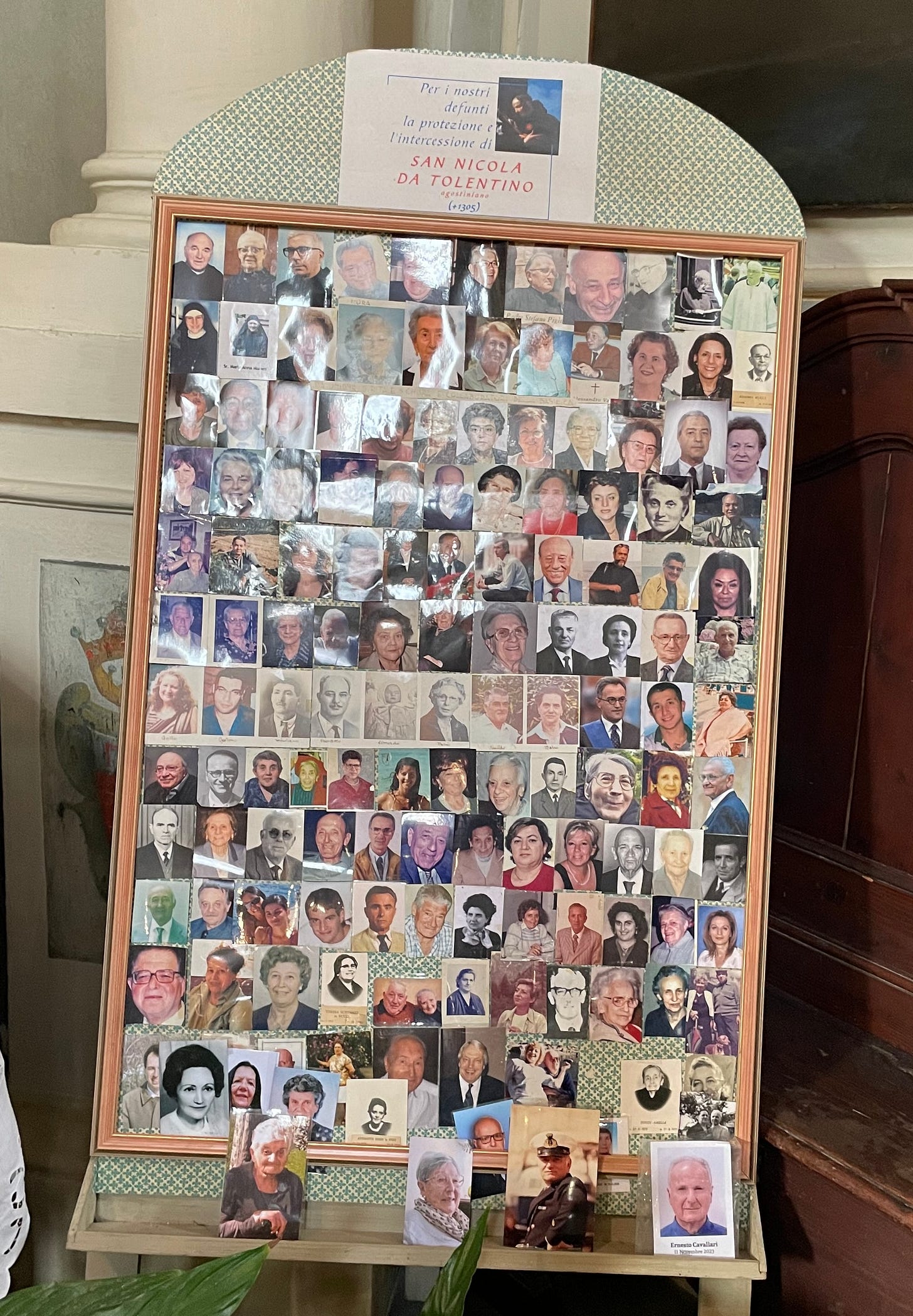

.In a side-chapel of the Basilica of San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna, there is a corkboard on a stand covered in little passport photos. The sign above reads “For our deceased, the protection and intercession of Saint Nicola da Tolentino.”

In Padua at the Basilica of Saint Anthony, a big pilgrimage site, Anthony’s tomb is covered in a chaotic disarray of passport photos. He is the patron saint of lost people and lost souls, and these are requests for them to be found.

When dealing with death and loss, Italians love picture portraits.

Green-Wood Cemetery, by contrast, is aniconic. The gravestones favour symbols: columns, vases, obelisks, crosses, Gothic spires, allegorized sculpture. Everything rises up out of the ground, pronouncing itself (phallically). Last names (SMITH, WILSON, JAMES) and family roles (FATHER, MOTHER, WIFE, SON) become sole descriptors as the grave favours symbolic gravitas to describe the kind of people who are dead underneath.

The closest I find to pictures are the portrait reliefs of Emily Frances Hall and George Henry Hall, who are looking at each other despite the circumstances. These retain the stiffness of the 19th-century Italian photographs, but they are not facing us and they are represented in stone rather than film—the Halls are far more distant, particularly as Emily’s sandstone face is eroding into a soft nothingness.

Basquiat is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery. I follow the pin of where he is on my phone and I expect some ridiculous artist thing to rival some of the 19th-century pomp that litters the cemetery. I put my phone away because I feel I won’t need help finding it—I’ll know it when I see it. I walk past it. After 10 minutes, I realise Basquiat must be one of a long line of near-identical, compactly arranged, short graves, far from the path. His grave has no pomp, not even particularly interesting detritus left from pilgrimages of Basquiat copycat artists (which abound, and should be coming here, but alas as we know they are lazy). The grave, like its close neighbours, is simplistic, squat, and grey. It reads only his name, “ARTIST,” and the dates of his birth and death, and, in the corner, the number 342 which I imagine is his plot in this line. Its detritus includes: multiple pencils stuffed into the half-inch space between the back of this grave and the one behind it, some painted and unpainted rocks, a shell, a gum in a blister pack, a tiny rubber band, discarded pens and sharpies in the dirt, and particularly sad looking dead flowers. I sit down in the patch of dirt in front of the stone and try to give him the respect he deserves, even while his cookie-cutter grave is covered in trash, but I realise I am sitting on top of a dead man and I get a bit freaked out and start to move. The truth is there isn’t anything interesting about Basquiat’s grave, it tells a short story of a person who died unexpectedly with not a lot of money, not the story of a genius Great artist. I find myself more interested in his neighbouring graves.

The graves down this line belong to people without the generational New York power to be buried alongside their 19th-century ancestors under a Gothic revival tombstone. If I can assume based on the Hispanic and Italian last names I’m reading, they are immigrants and minorities. And… their graves have photographs! The exact same kind, the awkward front-facing photo. So, removing ourselves from our graves is an anglo protestant invention? Or putting pictures of dead people in public is a non-anglo catholic impulse?

Death is something that is kind of impossible to understand and to picture, as is nothingness/everythingness (because our understanding of death is it is either endless nothingness or it could be one of a million different afterlife scenarios). It seems like symbolism is one of the only ways we can think about it: death is like a woman weeping, death is like stone, death is like an obelisk. But another way to depict it is to depict the living, or rather depict the dead with an image of who they were when they were living, which for a passerby is disarming and immediate and strange.

On the gate on the way out is a relief sculpture of Lazarus. The inscription reads, “Weep not, the dead shall be raised.” So it seems we don’t have to worry about it very much.

In Italy Cypress trees are commonly planted in graveyards and not allowed to be planted anywhere else